The Beatles 1963: A Year In The Life when everything changed forever

- Mar 20, 2023

- 9 min read

Phil Shaw

In winter 1963

It felt like the world would freeze

With John F Kennedy

And The Beatles

From the 1983 single Life In A Northern Town by The Dream Academy

The big freeze finally morphed into the great thaw – but changes to the cultural landscape which ran parallel to the coldest winter in decades left a permanent mark on Britain and beyond.

Spearheading the transformation were four young lads from Liverpool who had made a modest dent in the pop charts in late 1962, before the sea froze over and sport was snowed under. But as the Cape Cod-based author Dafydd Rees demonstrates in this entertaining and rigorously researched tome, 1963 was the year everything changed forever: the Year of The Beatles.

They began it waking up in a Hamburg flea-pit after their final show at the Star-Club. Returning to launch a Scottish tour in the Highlands, they played to two dozen people in Dingwall on a night so brass-monkeys they performed with coats and scarves on.

They ended it halfway through a 14-day run at London’s Finsbury Park Astoria – two sold-out shows per night – having already played the Palladium and the Royal Variety Performance. Once they conquered America in the New Year it was everything, everywhere, all at once for The Beatles.

Students of Beatlemania and fans of the Fab Four – both terms coined during this period of upheaval and excitement – have been spoiled in terms of literary appraisals and analysis of the art of John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr and its enduring impact. My list of must-reads would be headed by Revolution In The Head: The Beatles’ Records And The Sixties, by Ian MacDonald, followed by One, Two, Three Four: The Beatles In Time, by Craig Brown, and The Complete Beatles Chronicle by the band’s greatest historian, Mark Lewisohn.

Rees’s book is an important addition to the canon. He has restricted himself – although with 527 pages ‘restricted’ may give a false impression – to a forensic, day-by-day journey through the breakthrough year. He made visits to seaside resorts where The Beatles had week-long residencies, and spent weeks trawling local and national papers in the British Newspaper Library.

What gives the book its edge, however, is the testimony of hundreds of fans who answered the author’s appeal to come forward with their memories and snaps. Now in their late 60s or 70s, they described in vivid detail life-affirming and life-changing experiences.

Barbara Hodson, a Leicester teenager who went on to become a civil servant, returned from accompanying a school friend to a Beatles show in a theatre full of hysterical, screaming girls to tell her mother: ‘We didn’t hear anything. We didn’t see anything. But it was fab.’

Her words underline the generational divide which the group opened up. That hair… are they boys or girls? Those vocals… is it ‘real’ singing? The early fans are now ‘old’ but still revering The Beatles with their children and grandchildren.

Alongside their stories are the recollections of many who went on to work in the music industry, including a host of musicians. They include Rod Argent, soon to make the charts with The Zombies; Peter Asher, brother of actress Jane Asher (who became McCartney’s girlfriend in 1963) and a hit-maker with Lennon-McCartney’s World Without Love as half of Peter & Gordon; and John McNally of Cavern Club chums The Searchers, who reveals how they spurned the chance to cut the freshly written Things We Said Today.

Alongside the 60-year retrospectives Rees provides compelling contemporaneous cuttings and quotes. By way of context, the UK was ruled by a tired, discredited Tory government riven by the Profumo scandal. The satirical TV show That Was The Week That Was had begun chipping away at deference, but working-class or Liverpudlian voices were seldom heard.

The Teddy Boys had gone. Mods, skinheads and hippies were yet to appear, likewise music radio, although Ready Steady Go! would kick off in August. Pop was ‘safe’, personified by Cliff Richard. Bruce Welch of The Shadows (favourites of The Beatles), reportedly dismissed the mop-topped interlopers as ‘Nothing special. Once they [the songs] dry up, that’ll be the end of them’.

The notion that they were a flash in the pan was a common theme. Caroline Maudling, 16-year-old daughter of Chancellor of the Exchequer Reginald Maudling, said after appearing with Lennon on Juke Box Jury: ‘This is just a wild phase and will end as suddenly as it started, I’m convinced.’ (Edward Heath, a future Prime Minister, complained that The Beatles ‘don’t speak the Queen’s English’.)

The emergence of John, Paul, George and Ringo, as if from nowhere, caught the press off guard. In February the Daily Mail called Please Please Me ‘almost incoherent except for its solid, battering beat’ and informed readers they were ‘Kenny Lynch’s backing group’. The Romford Recorder reported ‘girls pelting the stage with cards and gifts for Beatle McKenzie (sic), who was 21 last week’.

As the year rolled on, and the No1s kept coming, the tone changed. With the bandwagon-jumping and gushing reviews came the backlash, Daily Mirror columnist Donald Zec deriding them as ‘four frenzied little Lord Fauntelroys who are making £50,000 every week’.

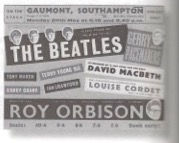

If they were making that sort of money, they certainly earned it. Brian Epstein, their manager, still had them criss-crossing Britain to play countless gigs -- including their 274th and last show at The Cavern. Soon the journeys and fame would be global. And all the time they were writing and recording the songs that became the soundtrack of our lives.

Rees has done a great service to anyone seeking to understand, enjoy or relive The Beatles’ epochal year (the first of them, that is). 1963 and all that is history in the same way that 1066 and 1215 are; the year the Sixties as a cultural construct truly began. If it isn’t already taught in schools and universities, it should be, with this book high on the reading list.

The Beatles 1963: A Year In The Life

By Dafydd Rees (Omnibus Press)

The sounds of 1963: A swinging playlist

Phil Shaw

This selection does not purport to contain the 10 best tracks of 1963, rather to give a sense of the music scene in Britain during the year in which The Beatles charged into our charts and hearts. That’s why it contains examples of ‘Beat Music’ as well as more durable musical trends such as the Motown Sound, The Wall of Sound and the Dylan-led folk/protest genre.

Jackie DeShannon: When You Walk In The Room

Not just one of the outstanding pop songs of 1963 but one of the best of all time, although incredibly it began as a B-side. DeShannon wrote and sang it, capturing brilliantly the agonies of unrequited love. The couplet ending with a rare use of ‘nonchalant’ is lyric-writing perfection, while ‘trumpets sound and I hear thunder boom’ encapsulates the conflicting emotions of infatuation. Throw in the guitar-hook intro and you can see why The Searchers pounced to take it to No3, having topped the chart in 1963 with another single by the farmer’s daughter from Kentucky, Jack Nitzsche and Sonny Bono’s Needles and Pins.

The Big Three: Some Other Guy

In the two years before Beatlemania took hold The Big Three rivalled the Fab Four for popularity on Merseyside. They signed to Brian Epstein, who sent them to Hamburg’s Star-Club and landed them a deal with the label that famously rejected his best-known clients, Decca. When ‘Beat Music’ swept the nation it seemed a shoo-in for Johnny Hutchinson, Brian Griffiths and Johnny Gustafson (later of Roxy Music) to gatecrash the charts. Their first 45, Some Other Guy – written by Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller and Richie Barrett and once part of The Beatles’ set – looked set to do it in the summer of 1963 only to stall at No37.

The Beach Boys: In My Room

Another enduring masterpiece that began life as the flipside when the record company rated it inferior to the Be True To Your School from the Surfer Girl LP. Brian Wilson wrote the melody and his songwriting foil Gary Usher helped develop Brian’s idea of his room as his ‘kingdom’, where he was safe from his abusive father. The harmonies on the first verse are an all-Wilson affair, with brothers Carl and Dennis pitching in. Before David Crosby joined the nascent Byrds he heard In My Room and thought ‘I give up. I’ll never be able to do that’. He later recorded the song with Jim Webb and Carly Simon for a Brian Wilson tribute album.

Helen Shapiro: Woe Is Me

Before the bitter winter The Beatles were slated to appear fourth (out of seven) on the bill for a package tour in early 1963 headed by London girl Helen Shapiro. The group liked her and sought her advice over whether to go with From Me To You or Thank You Girl as the next single. She would not turn 17 until September but her star was already waning. To try to halt the decline her label sent Shapiro to Nashville where she recorded this Jackie DeShannon and Sharon Sheeley number. Raunchier than her two chart-toppers from 1961 and seemingly well suited to the new era, it stands up well to modern-day scrutiny but petered out at No35.

The Marauders: That’s What I Want

The Stoke-on-Trent quartet were cited in one of the late Welsh rocker Deke Leonard’s memoirs as a group all their contemporaries looked up to. This, their debut single released in July 1963, was penned by prolific songwriters John Carter and Ken Lewis. Featuring a Lennonesque lead vocal and a guitar break reputedly by session king Big Jim Sullivan, it stood apart from Mersey Beat despite their numerous Cavern appearances. Ahead of its time, the record deserved better than to peak at No43. In September they were invited to play on Pop Go The Beatles on the BBC Light Programme but never built on this minor classic.

Martha & The Vandellas: Heat Wave

As male bands, especially from Liverpool, became all the rage in Britain, a production line of girl groups was rolling in one of America’s great northern industrial cities. Detroit’s own Martha Reeves fronted the Vandellas on a run of Motown dancefloor-fillers, with Holland-Dozier-Holland’s Heat Wave the first to breach the US top 10 and pave the way for Dancing In The Street, Nowhere To Run and many more. Their ‘burning desire’ did not initially catch fire across the Atlantic, but it would be covered by The Who and The Jam, while the Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian adapted its opening chord sequence for Do You Believe In Magic.

Faron’s Flamingos: Do You Love Me

The Beatles covered You Really Got A Hold On Me, Please Mr Postman and Money for their second LP in 1963 – but Faron’s Flamingos were the first Liverpool group to fuse Mersey Beat and Motown. Their raucous cover of The Contours’ Do You Love Me appeared in the spring, producer John Schroeder having brought people in from the street to dance and give the musicians a sense of playing live. It failed to sell: the label, Oriole, was too small to fund promotion and undecided over whether See If She Cares should be the A-side. Even so, it remains superior to hit versions by Brian Poole & The Tremeloes and the Dave Clark Five.

The Ronettes: Be My Baby

New York/New Jersey also had its girl groups, notably The Ronettes, Crystals and Shirelles, the first two coming under Phil Spector’s sway. The late producer’s biographer, Mick Brown, has argued that this number, with its memorable vocal by Veronica Bennett, was effectively a declaration of love for the woman who would become Mrs Ronnie Spector. Setting aside the debate about whether it is about romance or control – which started before Phil Spector was convicted of murder – it rivals the Righteous Brothers’ You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling as the quintessential Wall of Sound song and was a powerful influence on Brian Wilson.

Bob Dylan: Masters Of War

While The Beatles were busy churning out irresistible tunes with a devilish beat but somewhat limited lyrics, Dylan combined poetry and protest after the Cold War threatened to overheat during the Cuban missile crisis. This track from the Freewheelin’ LP gave voice to those who campaigned for nuclear disarmament. It was ‘inspired’ by President Eisenhower’s talk of a ‘military-industrial complex’ on making way for John F Kennedy. Dylan would grow closer to George Harrison, yet his early acoustic style clearly filtered through to songs such as You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away and Working-Class Hero by John Lennon.

The Beatles: All My Loving

The jaunty innocence of this Paul McCartney song contrasted sharply with the more acerbic contributions to their second album, With The Beatles, by his usual collaborator. Untypically for its writer, the lyric came first. It was never a single in this country but was strong enough to be played during their debut on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. The late Ian MacDonald, the most authoritative chronicler of the influences, innovations and fine details of each of the 186 tracks they officially released, from Love Me Do to I Me Mine, wrote: ‘Their rivals looked on amazed as songs of this commercial appeal were casually thrown away on LPs.’

Comments