Pulp: Spike Island and an anniversary of anthems

- Phil Shaw

- May 15, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: May 31, 2025

Phil Shaw

By the time they got to Spike Island they were 30,000 strong, to adapt Joni Mitchell’s line about the ‘stardust and golden’ multitudes who converged on the Woodstock Music & Art Fair in 1969. ‘Everywhere,’ she sang, ‘was a song and a celebration.’

There were certainly songs at the one-day festival headlined by Manchester’s Stone Roses 21 years later at Spike Island – artificially constructed land that once housed the chemical industry in Widnes, midway between Liverpool and Manchester – but the celebratory mood was reportedly conspicuous by its absence.

With a summer of British festivals imminent, Pulp are about to release a 7" single from their reunion album More. Appearing just four days before the 35th anniversary of 27 May, 1990, when the Roses headed a line-up bolstered by DJs from the rave scene, a Zimbabwean drum orchestra (sic) and rock-reggae fusion act Ruff Ruff And Ready, the song is called Spike Island.

Its arrival means that Pulp’s singer and lyricist Jarvis Cocker has now written two tracks, three decades apart, which draw on the much-mythologised event on the banks of the Mersey. Neither could be described as a celebration. (Strangely enough, just as Joni missed Woodstock because she was appearing on the Dick Cavett Show in New York City, Cocker did not attend the Roses gig. The band’s guitarist Mark Webber was in the throng, however, and recalls strong winds and dodgy sound quality, adding: ‘The vibe wasn’t there.’)

Cocker’s first composition referencing the notoriously chaotic gathering was Sorted For E’s & Wizz, from the 1995 album Different Class. The title came from a woman he met in The Leadmill, the fabled music venue in home-town Sheffield. Drug dealers were moving through the crowd, she said, asking: ‘Everyone sorted for E’s (Ecstasy) and Wizz (Speed)?’

He would insist it is not an anti-drugs song, merely a ‘factual’ look at what happened, although some critics felt it stigmatised rave culture as being solely about getting off your head. I regard it as satirical, and the storytelling is characteristically vivid.

In the middle of the night

It feels all right

But then tomorrow morning

Ooh, ooh, then you come down

Ooh, ooh, then you come down

Ooh, what if you never come down

This is all a long way from Mitchell’s optimistic, arguably naive, take on a counter-cultural coming-together blighted by rain, mud, unsanitary conditions, food shortages and gate-crashers; an estimated 450,000 reached Bethel, where Woodstock was actually held, yet only 186,000 tickets were sold.

Written in a Manhattan hotel room and released on 1970’s Ladies Of the Canyon, her paean to the so-called Woodstock nation was not the first festival song. That distinction may belong to Eric Burdon & The Animals’ sitar-driven Monterey, eulogising the seminal 1967 event in California. Mitchell’s poetic imagery contrasted sharply with Burdon’s roll-call of acts, from Jefferson Airplane to Ravi Shankar via The Who.

David Crosby also created a Monterey-influenced number. Tribal Gathering was initially inspired by the Love-Ins and Be-Ins in San Francisco during the days of nascent hippiedom. An eerie, beautiful song, co-written by Chris Hillman and plainly indebted to Dave Brubeck’s modern-jazz classic Take Five, it surfaced on 1968’s Notorious Byrd Brothers, by which time Crosby had been ousted from The Byrds.

Spike Island is a far cry, too, from Melanie’s stirring evocation of Woodstock, Lay Down (Candles in the Rain), recorded with gospel choir the Edwin Hawkins Singers and a huge US hit. She felt ‘a sense of community… a positive wave of human power flowing into me’. Performing there was ‘a life-changing experience’.

On Sorted For E’s & Wizz, Cocker chronicled something flowing into his mind and body, possibly life-changing too, if not in a positive way.

And this hollow feeling grows and grows and grows and grows

And you want to call your mother and say

‘Mother, I can never come home again

Cos I seem to have left an important part of my brain

Somewhere in a field in Hampshire’

According to The Guardian, Pulp’s Spike Island is ‘a metaphor for disappointment’. It can also be seen as a dark, distant counterpoint to Woodstock, whose message of peace and love reached an audience beyond the ‘freak’ diaspora thanks to covers by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and Matthews Southern Comfort (a UK No.1).

Consciously or not, Cocker’s new song has distorted echoes of Mitchell’s anthem, even if its lyric is untypically oblique for the class-conscious writer of Common People and Disco 2000. They sounded like the latest in the English kitchen-sink vignettes stretching from Dead End Street to Up The Junction and Our House.

Where she implores us to return to a green, idyllic Eden – ‘We’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden’ – Cocker plays on the title of the early Dutch master Hieronymus Bosch’s 500-year-old triptych about the perils of temptation, originally titled Garden of Lusts:

I was conforming to a cosmic design

I was playing to type

Until I walked back to the Garden

Of Earthly Delights

And while she sings of walking with a stranger who tells her he is ‘going down to [Max] Yasgur’s Farm to join in a rock ’n’ roll band’, he appears to demystify, or debunk, his chosen profession with self-mockery in the final line of one verse:

I was born to perform

It’s a calling

I exist

To do this

Shouting and pointing

If you’re wondering how this relates to the Spike Island show of May 27, 1990, Cocker brings it all together with the title line, using the on-stage MC’s exhortation reported to him by those who were there.

Spike Island

Come alive

By the way

The ‘by the way’ is not, I suspect, mere line-filler but Cocker’s way of saying that instructing people to ‘Come alive’ is as meaningless as throwaway phrases such as ‘By the way’.

The music was written by long-time Cocker collaborator Jason Buckle, who lends his percussive skills to Pulp and was also at Spike Island. It has an ominous but thrilling feel, Webber and Candida Doyle creating a relentless, almost industrial backdrop with synchronised guitar and synthesiser, like a huge piece of sawing or drilling machinery.

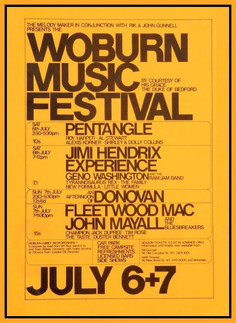

Are Cocker’s sister songs a cynical, or moralistic, take on festival culture? I wasn’t at Spike Island and never fancied Glastonbury but I have been to dozens, starting with Jimi Hendrix at Woburn Abbey in 1968, taking in Buxton, Hollywood, Womad, Leeds, Moseley, Latitude, End of the Road, Shrewsbury Folk and LoopFest and Green Man.

At the early ones there were frequent loudspeaker appeals to friends of people having bad trips. The whiff of weed remains in the air, but these days people are more likely to be scoring a Goan fish curry and getting sorted for hazy IPAs.

At Woodstock, Joni aimed to ‘camp out on the land to try an’ get my soul free’. Widnes is a bit different: a rugby league player I interviewed ahead of a Wembley cup final, whose day job was in a chemical plant, reckoned that if you left the town you died of fresh air. Jarvis’s updates may inspire some near-sixtysomething Spike Island veterans to venture back there, but they will have to share it with wildlife, walkers and the ghosts of their youth.

Comments